I am told that jetlag hits harder the older you get so I accepted my lack of sleep on the day of my presentation without much protest, the entire night a feverish array of tossing and turning, multiple restroom trips, the shuttering of the eyelids and their eventual rising when the light filtered through the curtains and I spotted with my crusted eyes, A.’s meditative silhouette in the corner of the hotel room.

On the day I was due to present, my giddy anticipation before the presentation had to be tempered by a sobering trip to Kahnawá:ke, a First Nations territory located on the southern shore of Québec’s St. Lawrence River. Dwayne, a history teacher turned education consultant and our guide for the day, spoke somberly about the history of the Iroquois, a history of immense loss and the long, ongoing process of reconciliation. I thought I detected some chagrin when Dwayne said that he sees himself as a “floater,” someone who is in-between, having not adopted the Catholicism brought over by French colonizers nor fully reconnected with the dispossessed Longhouse culture of his people. But I also thought that I sensed some pride when Dwayne said that his daughter speaks better Kanienʼkéha than he does.

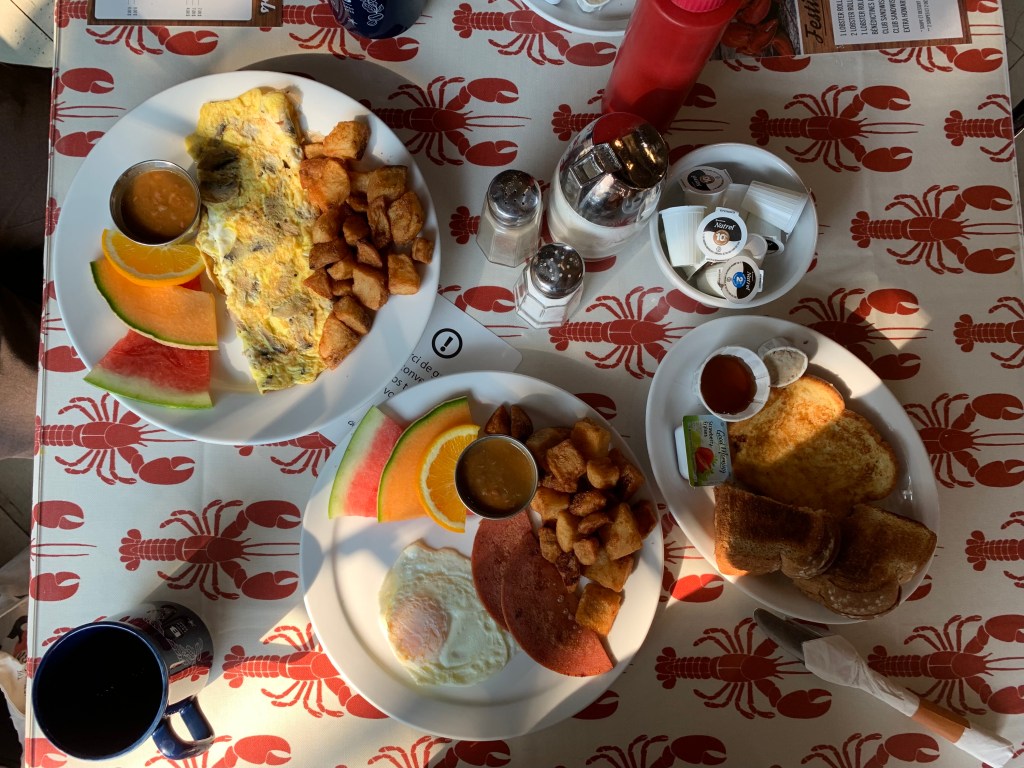

By late noon I was awake for over 16 hours. A catered picnic lunch offered a brief respite: cornbread, goat cheese, wild rice salad, and watermelon ice under patio umbrellas overlooking the river. I combed through some of the notes I jotted down:

The Truth & Reconciliation Commission of Canada was formed in 2008 to rectify the legacy of residential schools, a legacy that involved taking kids aged 4-17 away from reserves so that they could be assimilated into “Euro-Canadian culture.” The last federally funded residential school closed in Canada in 1997. In 2021, 215 possible unmarked graves were discovered under a former residential school in British Columbia. A memorial site in Kahnawá:ke was set up. People left flowers, bears, and children’s shoes.